Vince Guaraldi's Brilliant Use of Repetition

This is Linus and Lucy by the Vince Guaraldi Trio from the Charlie Brown Christmas Special – which explains why it’s played at Christmas each year, or at least why it’s on my Christmas playlist.

It’s Infectious. An Ear-worm. It’s been stuck in my head for a week. Why is that? An effective use of repeated material.

Repeats in music

It’s a delicate balance in music. You want there to be a nice blend of new material and repeated material. As humans, we like the thrill of novel experiences and the comfort of repeated experiences. Same in music. Our ears like hearing new things, followed by the ability to soak it in. These must be balanced – too much novel is jarring, and perhaps forgettable; and of course, familiarity breeds contempt...or boredom. Most songs or pieces are explorations of 1 or 2 main ideas – a nice blend of the novel and the repeated. Of course, both never repeating and over repeating can be used to great effect as well, but that’s for another time.

Ostinatos

The first thing we hear is a short repeated bassline. This bassline will become the foundation on which the opening section is built. We hear that in a lot of music. Of course, it can be a bassline [Seven Nation Army], or it can have a more melodic quality, [Miles Davis’ So What; Dave Brubeck’s Take Five]; it can be just rhythmic [You Really Got Me], or it can stack multiple repeats on top of each other [Billie Jean].

We can call these repeated phrases either an ostinato, or a loop. Also related: Vamps, Licks, and Riffs. We can see that the rhythm for this will stay constant while the pitches will change to fit the harmony.

On top of this ostinato comes the main theme for the song, which immediately causes dancing. I mean, tell me you don’t want to dance like that. The gang putting on an absolute masterclass of dance moves.

2. Repeats in the melody

There are also repeats that occur in the melody. New ideas are reinforced by repetition.

If we breakdown the melody, there are essentially two ideas [Figure 1, Figure 2]. Crazy thing is: the melody here is only three notes. This over here is just figure 2 backwards, sometimes called a retrograde. The first phrase plays 1 and 2, the second phrase only uses figure 1. That exact melody is played again to complete the idea – which I’ll use a small ‘a’.

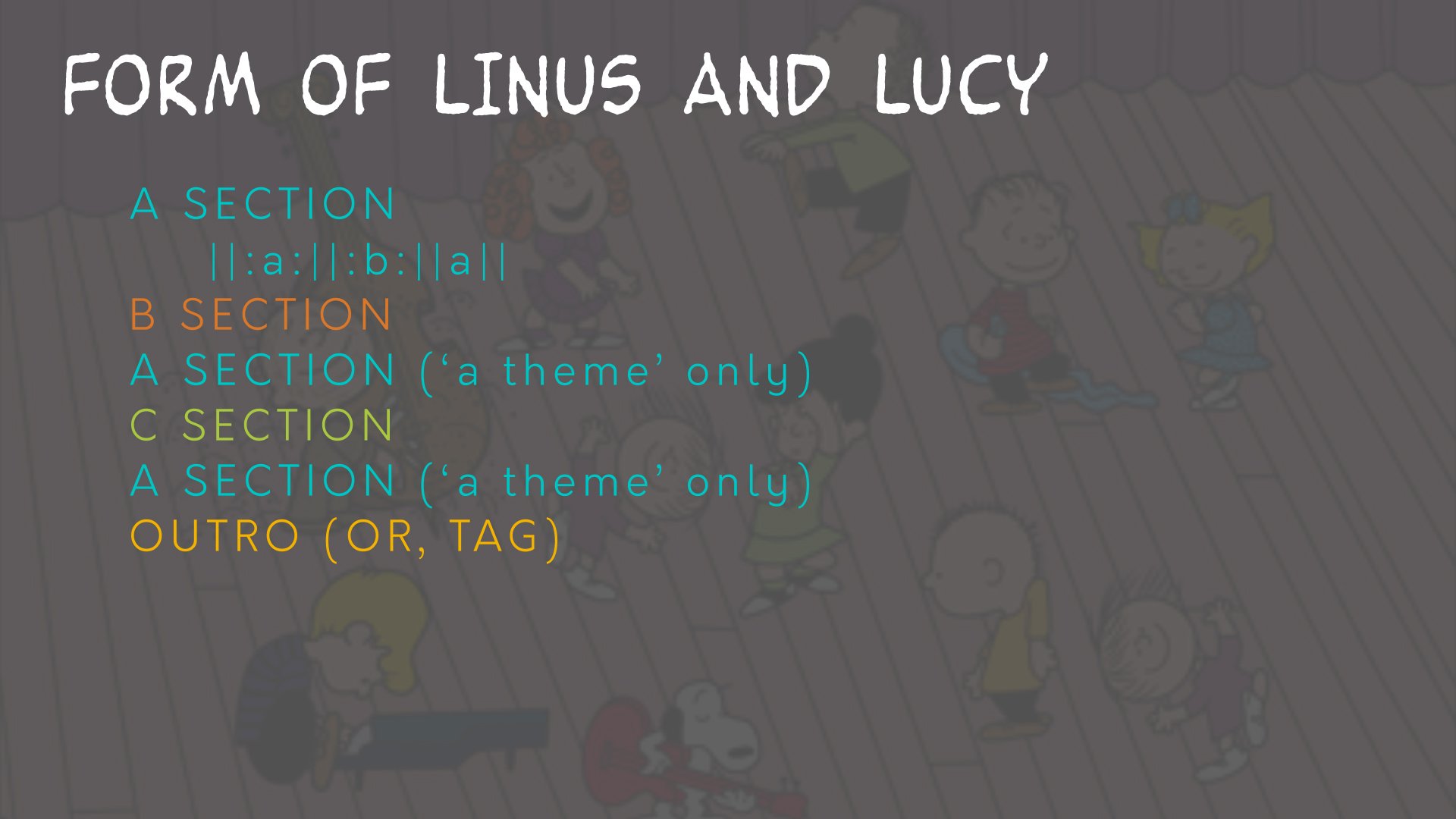

The second part of this section [small ‘b’] is also made up of two basic ideas, we’ll call them [Figure 3] and [Figure 4]. Each figure repeats 3 times. The ‘a theme’ returns after this, but it is simple enough, catchy enough, and repeated enough that by now the audience could probably sing along. The ‘a theme’ repeat gives us an aba form, or ternary form, for the opening section. This “form within a form” is called an “internal form”.

3. Contrast with non-repeating sections

Another delicate balance in music is between similarity and contrast. We generally want pieces to sound cohesive – like all of the material goes together; but we also don’t want it to be monochromatic. Contrast is a good way to do this. There are a lot of different types of contrast, fast/slow, loud/soft, changing the instruments...There are two other sections in this piece, and so in contrast to the opening section, there’s not as much melodic repeating - this is a great way to keep what does repeat from going dull.

Even though the Second Section has less repeats, the section is still built on two contrasting ideas: the block chords [figure 5] – which are based on repeated chords, and the non-repeating melodic arpeggiation [figure 6].

The Third section is by far the biggest contrast. It changes to a compound meter, it features a walking bassline, and as a whole, the melody has an improvisatory nature to it.

4. Repeats in Form

Another way we can repeat is in the structure of the music – whole sections can be repeated. A very important concept in composition is the idea of the hook [Hook: Definition]. In a classical context, it might be known as a motif, a theme, or a subject. The point with all of these is to be somewhat of a thesis statement for our ears. And this is a very strong hook [hook, with dancing] – you want your hook front and center multiple times.

For Linus and Lucy that structure looks like this:

This is something that we also see in Für Elise...from Schroeder’s favorite composer. We often think of this piece as just the A section – another good hook. If we look at the structure for this one, it looks familiar.

In Western Classical music, this is called “Rondo” form. Generally, we call the A theme in rondo form the refrain, and the other themes episodes. As we saw in both pieces, the refrain is in contrast to each episode. In the Classical Period, it was conventional for each episode to be in a related key to the refrain. There’s really no limit on how many episodes there can be, although many Rondos stick to ABACA.

This form may seem familiar. Most modern songs will have a structure that alternates between verses and chorus, with a bridge. Since we’ve called the hook the “a” theme, that would give most songs this structure:

Meaning a song starting with its chorus would have this structure:

Effectively the same form we’ve been looking at. But remember, this form is not rigid. This is a codification of a common pattern. And modern song form needs its own video for in depth discussion.

6 Ways Effectively Use Repeats

So how does Linus and Lucy effectively use repeats? 1) In the ostinato, 2) repeated notes in the melody, 3) in your melodic structure, 4) repeat entire sections – especially your hook, 5) blend repetitions with the novel, 6) cleanse the palate with contrast. All with moderation.

![How The Punch Brothers Converted a Song from 4/4 to 5/8 [Score Study #2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5281a267e4b04f95c7231e30/1665687621641-QI2ZW6DONNOSXK8XKEFQ/002ChurchStreetBlues.jpg)