How Mendelssohn Writes A Theme

This is Melodie No. 2 in C# minor, from Fanny Mendelssohn’s Op. 4, which was first published in 1847 – the year of the composer’s death. The entire piece is just over a minute long, consisting of exactly one theme which runs the length of the piece.

That makes it a great example for studying the construction of themes. With a theme, we have motifs, phrases, and periods all present, but it is how they are constructed that tells the story. See, with a theme, we can have motivic development, harmonic expansion, and we can look at the big picture of overall melodic contour.

It begins with a leap of 6th, which is immediately against our expectations. We would more often expect to see a leap of a perfect 4th, from sol to do. But instead we get a 6th, from sol to me. The opening motif, jumps around, eventually making its way to the tonic. But again, it’s destabilized. It’s a tonic C# in the melody, but it’s played over a broken A major chord, or Major VI. Perhaps in the classical period it would have sounded more predictable, with a strong establishment of tonic, and a perfect authentic cadence to close the first phrase. But Mendelssohn doesn’t give us the satisfaction of predicting where she is going. Additionally, the phrase markings tell us that the phrase actually extends all the way to the end of the measure – once again, an E, the relative major – which seems to be the symbol for destabilization. The motion of the accompaniment is relentless. It never stops moving. This would be a very different piece if the harmony was made up of sustained dotted half notes.

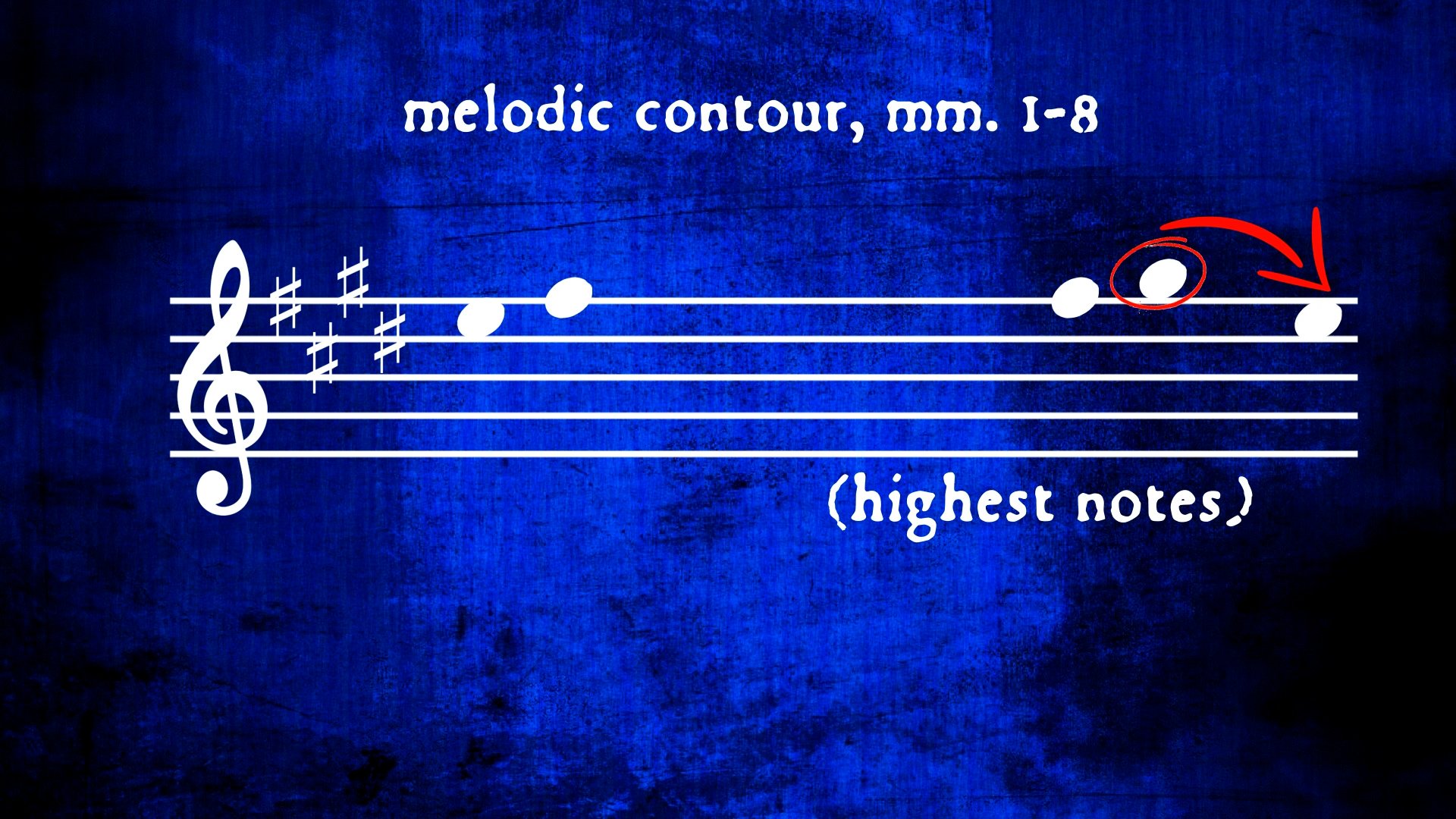

In fact, these ideas of destabilization and unexpectedness permeate the entire theme. Look at the following phrase – it’s building, it’s trying to go somewhere, but it somehow loses its energy, and in the end, it doesn’t rise, it falls. But it’s going to try again, and it will keep trying throughout the piece. Perhaps another word to add to “destabilized” is uncertainty. The theme being unpredictable helps the listener feel the uncertainty that surrounds the struggle. But, for all of the struggle, it seems stuck. This is where overall melodic contour is really important. If we isolate a few structural melodic notes, we see highest this piece has been able to climb so far is G#. But the second that it made it to G#, it falls back to E. Like it always does.

And that should close the first section of the theme. We’ve had a return to a prevailing tonic harmony. Sure, it was IV-I motion, but that’s not too unusual. And sure, we’ve once again landed on the 3rd scale degree. But what really makes sure that we don’t feel at home, is the harmonic shift, with the introduction of a D natural. We’ve moved to V/IV. Why? Are we modulating to A major? Well, no. What just happened? Mendelssohn has added a four-measure tag to the end of this opening section. And the allusion to A major? A brilliant bit of foreshadowing telling us where the B section of this theme is going. Turns out that unexpected A major chord in measure 2 could have been giving us a hint at the secondary key of the piece. This tag also introduces A natural as the new highest note in the piece.

The B section opens with a stepwise ascent to the A, but it gets stuck there. So, it tries again. This time falling all the way back down to E. The B section is mostly in A major, but is more harmonically tumultuous than the A section – which serves to underline the struggle occurring in the melody. No matter how hard it tries, the melody cannot seem to ascend above that. Although, it will rise to the A natural 7 more times. The theme is nothing if not persistent.

The B section climatically returns to the A section with the first and only forte marking in the piece. This forte doesn’t last though. It drifts back to quietness halfway through the phase. And much like in the opening A section, there is a cadence after 8 bars – this time however, it finishes on tonic. We could be done here, we’ve made it home. But Mendelssohn once again adds a four-measure tag, this time, the melody finally ascends all the way up to the high C#. Not triumphant and loud, but tenderly. Almost as if the amount of fighting it took to get to this point has taken away all energy the theme once had.

Fanny was no stranger to this struggle – a fight to ascend that is constantly frustrated. Her father once wrote to her that “music will perhaps become his profession (ie, her brother Felix), while for you it must be only an ornament.” And in fact, some of her works were published under her brother’s name. Fanny herself said of this struggle: “It must be a sign of talent that I do not give up, though I can get nobody to take interest in my efforts.”

Of course, much of music is about some form of struggle, but this melody, like so many other works of Fanny Mendelssohn, seems to embody the struggle, and labor of someone longing to ascend, and have their own voice rise to the top, and be heard, and valued in its own right.