The Basics of Time Signatures

So, when you're going along a sheet of music, you'll notice these vertical lines that go down the staff. These are called measures. Most western music is a pattern of beats. Measures show us where those patterns begin and end.

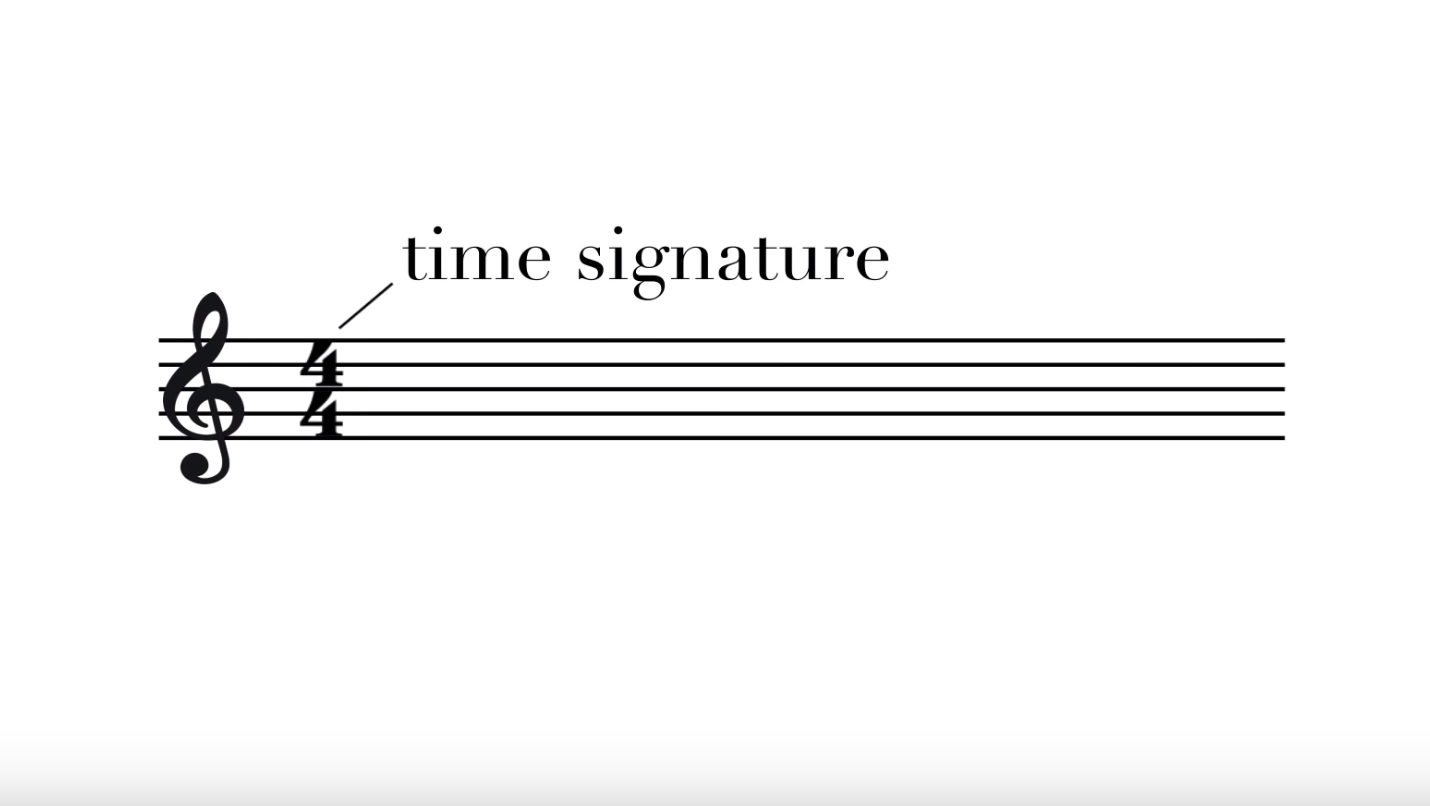

Time signatures tell us how long the measure is and what kind of note gets the beat.

A time signature contains two numbers. They are on top of each other like a fraction, but they are not a fraction. The top number tells us how many beats are in each measure, and the bottom number tells us which note is given the beat.

For example, the most common time signature is 4/4. This means there are four beats in the measure and the quarter note gets the beat.

You mathematicians are looking at me going 4/4 equals 1. Yep. Still not a fraction.

We can have as many or as few beats per measure as we want. If we have 3 beats and the quarter note gets the beat, it's 3/4. If we have 2 beats, 2/4.

If we have 47 beats and the quarter note gets the beat it would be 47/4. To my knowledge no piece of music has ever been written in 47/4.

And I know someone watching this just thought to themselves "Challenge accepted"

What about measures that don't give the quarter note the beat?

If the 8th note has the beat, the bottom note is an 8. If it's the half note, it's a 2. If it's a 16th note, it's a 16. If it's a whole note, it's a 1. Makes sense, right?

Pretty much any combination of numbers will work, so long as the bottom number is a power of two. Yes, to answer your question, it is theoretically possible to have a bottom number that isn't a power of two, and yes, some composers have irrationally used them, but we aren't going there.

Next time we will look at the different ways that we can classify these time signatures.